Utilizing Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs)

What is it?

Supreme Audit Institutions (SAI) are independent national oversight bodies, largely responsible for auditing a government’s revenue and spending, helping to ensure full transparency and accountability, and even the performance of government bodies and ministries in using public funds efficiently and effectively. Structures, mandates and reporting relationships of SAIs vary, and thus, these institutions can play different accountability roles in different countries. Many SAIs independently support parliaments in performing oversight of government budgets and spending. However, many of them are playing an even larger role in accountability – including some with judicial authority – to ensure that government programmes are in compliance with laws and regulations, or even undertaking performance assessments to determine the effectiveness of a government’s activities.

Why is it important?

As a key player in ensuring transparency and accountability of any government’s budgets and programmes, SAIs can play a very important role in assessing progress on the implementation of the SDGs and the 2030 Agenda. SAIs can contribute in many ways. These include:

- Undertaking independent performance audits of a government’s SDG implementation efforts;

- Providing checks on a government’s budget allocation and expenditures;

- Ensuring compliance of a government’s programmes with existing laws and regulations; and

- Assessing the readiness of a national government to implement the SDGs and a government’s ability to report on the SDGs, including the reliability of its data production capabilities to support this reporting.

The existence and effectiveness of SAIs can also contribute directly to a country’s implementation of SDG 16, particularly in regard to targets around fostering transparent, effective, inclusive and accountable government institutions.

How can it be used?

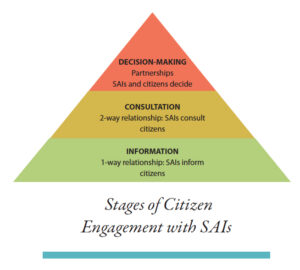

Civil society can engage with SAIs in a variety of ways. Such engagement can require time to build trust between civil society, SAIs and governments, and safe spaces for dialogue. Civil society should consider the politics and incentives of the different actors inside and outside of government to strengthen accountability. Starting engagement from a negative standpoint may discourage respective actors from supporting each other in their accountability efforts. The ways to engage include:

1. Support and partnership:

- Communicate with SAIs to understand their role and reports;

- Identify champions within SAIs that will work closely with civil society and invite them to engage;

- Conduct a context analysis and stakeholder mapping with SAIs to understand and act on strategic opportunities to ensure action on audits and issues of concern to the public; and

- Offer support for SAIs in planning, monitoring, reporting and follow-up process. CSOs can: provide topics or issues of concern for SAIs to audit; report fraud, waste and abuse via “hot lines”; engage in the execution of the audit through joint audits or social audits, including verification with affected citizens; disseminate audit findings and recommendations; and engage audited entities to ensure the recommendations are acted upon.

2. Advocacy:

- Advocate to ensure SAIs have the mandate, independence and resources to function effectively;

- Encourage SAIs to report on government programmes, including planning, spending and effectiveness, through an SDG lens;

- Advocate to ensure SAIs have the necessary information, from national to local authorities, to publish their audit reports in a timely, accessible manner; and

- Use audit reports in civil society advocacy work, including engagement with the government, legislature, media and the public.

3. Raise awareness:

- Launch public awareness campaigns that raise the profile of audit reports and educate citizens about the role SAIs play in holding governments to account. Such a campaign could be built around a database that tracks what the government is doing to address audit findings;

- Encourage open debates in parliament on SAI reports, that include civil society and citizens; and

- Work with oversight bodies to establish an annual “Accountability Day” whereby legislators review recent government performance. This could take place around the time the government announces the subsequent year’s budget.

Key Resources

• The Basics of Supreme Audit Institutions – Citizen Engagement, by Asociación Civil por la Igualdad y la Justicia (ACIJ).

• International Budget Partnership Resources on Audits.

• Accountants with Opinions: How Can Government Auditors Drive Accountability? Produced by International Budget Partnership.

• Citizen Engagement Practices by Supreme Audit Institutions.

• SAIs Engaging with Stakeholders Guide, produced by INTOSAI Development Initiative.

• Does collaboration with Civil Society strengthen accountability institutions? An Exploration.

• INTOSAI Journal – The International Journal of Government Auditing (the Journal) is the official publication of the International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI).

• The Impact of Performance Auditing: A Practice Friendly Review.

Case Study: Citizen Participation to Strengthen Oversight

Colombia: The Comptroller General of the Republic of Colombia (CGRC) actively promotes citizen participation in the oversight process. Colombia’s SAI developed a guide on joint audits with CSOs and citizens affected by public interventions. The actors provide input throughout the execution of audits: on-site; at meetings and roundtables; or through reports and any other forms of information that can help the SAI improve the audit process. CGRC has “worked to develop a civil and fiscal culture among citizens. From 2006 to 2010, it carried out 2,232 outreach activities, benefiting 281,861 citizens,” according to Practical Action. It has also: “established accessible channels for receiving citizens’ input and incorporating it in the audit process [and] from 2006-2010, the CGRC implemented 120 coordinated audits and created 763 citizen oversight committees. To ensure these mechanisms’ success, it carried out 4,964 training activities, enabling 177,196 citizens to actively participate in the oversight process.”2

South Korea: In South Korea, the Audit Office established a complaint hotline and whistle-blower mechanism through which citizens can report areas of suspected irregularities or corruption and can request audits. The hotline collects “reports on unjust handling of petitions by administrative agencies, complaints, and particularly behaviours such as unjustly refusing receipt and handling of petitions on the grounds that they may be later pinpointed by audit and inspection.” The hotlines also receive “reports of corruption and fraud of public officials, including bribery, idleness, embezzlement and the misappropriation of public funds.” This mechanism has been widely disseminated in South Korean society and has a dedicated page on the SAI’s website.3