Pursuing Law Reforms, Strategic Litigation and Legal Empowerment

What is it?

Law reform or legal reform is the process of analysing current laws and advocating and carrying out changes in a legal system, usually with the aim of enhancing justice or efficiency. There are four main methods of reforming the law: (a) repeal (removal or reversal of a law), (b) creation of new law, (c) consolidation (combination of a number of laws into one) and (d) codification (collection and systematic arrangement, usually by subject, of the laws of a state or country).1

Litigation means taking a case to court. Strategic litigation refers to public interest litigation that seeks to bring about a significant change in the law – e.g. clarifying, amending or extending the law in support of an overarching law reform objective – by taking an individual case to court.2 The people involved in strategic litigation cases are typically the victims of human rights violations – by the government or other powerful actors – that are also experienced by other people. Thus, strategic litigation often focuses on an individual case in order to bring about a systemic change for a much larger group of people.

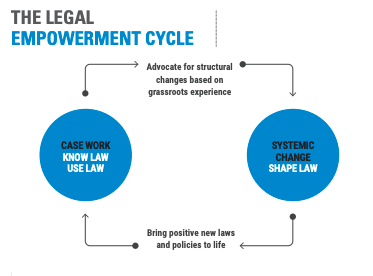

Legal empowerment enables people to know, use and shape the law. It starts from a grassroots orientation, as opposed to the top-down approaches of law reform and litigation. Legal empowerment is about strengthening the capacity of all people to exercise their rights – either as individuals or as members of a community – and ensuring that the law is available and meaningful to citizens. Building community power is central to legal empowerment.

Why is it important?

Despite the voluntary nature of the 2030 Agenda, both law reform and strategic litigation may be used to promote accountability for the SDGs. Law reform is essential for achieving a number of specific targets under the SDGs3 as well as to ensure there is overall consistency between a country’s national laws and the SDGs. Law reform may also be used to further accountability for the 2030 Agenda by ensuring that there is an enabling legal framework and environment for people to hold their governments accountable for SDG progress. For example, law reform may be used to ensure that civil society can provide input into public policy decision-making or that they have adequate access to judicial and other mechanisms to hold governments accountable.

Strategic litigation may also be used to review the soundness, legality and constitutionality of public policies, laws and official conduct as they relate to SDG implementation.4 Additionally, strategic litigation can be used to hold a government accountable for the implementation – or lack thereof – of laws themselves. In particular, litigation may be used where there is overlap between the provisions of the SDGs with the human rights and/or constitutional provisions of a country. For example, civil society may challenge and seek to improve access to basic services for vulnerable groups (SDG target 1.4) where the right of such access is provided for by the country’s constitution or by international human rights treaties to which the country is a party. Where the government’s actions undermine access to basic services or disproportionately harm particular individuals or groups, strategic litigation may result in the government’s having to justify its actions, take a certain course of action or establish an oversight mechanism that furthers accountability.5

In addition to law reform and strategic litigation, legal empowerment is also important in ensuring accountability for the SDGs. Legal empowerment is about strengthening the capacity of all people to exercise their rights – either as individuals or as members of a community – and ensuring that the law is available and meaningful to citizens. Approaches to legal empowerment may include legal education, information, advocacy, organizing and/or mediation. It is often promoted by a large frontline community of paralegals who are trained in law to assist citizens in finding concrete solutions to instances of injustice. Legal empowerment approaches engage the grassroots level, especially important for SDG implementation, follow-up and review at national and subnational levels. In turn, this can lead to more integrated and systematic approaches to SDG implementation.

TIP

TIP

How can it be used?

CSOs seeking to use law reform to promote accountability for the SDGs should consider engaging in the following actions:

1. Compare SDG targets with existing laws to identify any inconsistencies or gaps – It is critical for CSOs wishing to engage in law reform to undertake an initial gap analysis of existing laws and the SDGs in order to assess key areas for law reform. This analysis can then help inform decisions about which law reforms to prioritize.6

2. Raise awareness about existing laws and rights in relation to the SDGs – CSOs should raise awareness of existing laws and/or rights among citizens, including how laws may positively or negatively impact the achievement of the SDGs. By raising awareness, CSOs are more likely to be successful in garnering support for law reform proposals. Awareness-raising can target general members of the population as well as those in positions of power, such as members of the government and the judiciary. CSOs may also wish to engage various stakeholders – such as paralegals – to help people understand the law and their rights.

3. Engage with relevant ministries and legislators – The most common avenue for pursuing law reform is through working with the relevant ministries within the executive branch of government responsible for proposing law reforms. In many countries, it is also possible for legislators to propose new laws or amendments.7 To engage, CSOs should:

- As a starting point, determine how the law-making process works and which body in government or legislative body is responsible for actually drafting laws.8

- Educate and lobby key ministers, legislators and/or government officials on the issue for law reform.9

- Offer technical advice or support to the ministry, legislator or office responsible for legislative drafting to develop a proposal for law reform. Such support may include providing a draft law or model laws from other jurisdictions for consideration.10

- Offer practical support to the ministry, legislator or office responsible for legislative drafting to undertake or facilitate public consultations to inform the draft law.11

- Once a draft law is tabled for consideration, participate in any public hearings on the law by making oral or written submissions to legislative committees.12

TIP

TIP

Where law reform is unsuccessful or existing laws align with the SDGs but are not being implemented effectively, CSOs may seek to use strategic litigation to promote accountability for the SDGs. CSOs seeking to use litigation should consider engaging in the following actions:

1. Assess whether a particular SDG target is protected under the country’s constitutional, human rights or other law – Although the SDGs are not legally binding, it may be possible to make claims within national judicial mechanisms to hold governments accountable, where SDG commitments overlap with existing legal or constitutional guarantees.14 Similarly, it may be possible to pursue national litigation for the SDGs where a country has ratified an international human rights treaty that overlaps with the provisions of the SDGs.

2. Determine whether the government’s actions or failure to act constitute a violation of the law – CSOs should assess whether the government’s actions have violated an existing law or right in relation to the SDGs. In some cases, litigation may be pursued where a new or amended law is not being properly implemented or where the government is slow to dedicate resources to implementation.16 In many cases, it will be open to interpretation as to whether the government is violating the law, which may be resolved through litigation by the courts clarifying and providing guidance as to how the law should be interpreted.

3. Establish whether you have the right to pursue litigation against the government – In some cases, CSOs, individuals or groups may not have “standing” or the right to pursue litigation against the government unless they can demonstrate direct harm, harm to others who are unable to pursue litigation, or they have been granted “standing” under the law.

4. Seek professional legal assistance and support – Strategic litigation is costly, time-consuming and often requires the assistance of legal professionals who are trained to conduct litigation. Accordingly, CSOs should try to identify sources of pro bono or free legal advice or have lawyers as members of their civil society coalition.17 There are some legal groups who are sometimes willing to provide free advice such as the American Bar Association (ABA) or the International Development and Law Organisation (IDLO).18

Key Resources

• Advocacy: Justice and SDGs (2016), by the Transparency, Accountability and Participation (TAP) Network is a useful toolkit for civil society, activists and policy practitioners who are working to promote legal empowerment and access to justice in relation to the SDGs.

• The SDGs-enabling Law Reform Drive is a global initiative launched by a consortium of international law firms that seek to help developing countries undertake law reforms aimed at enabling effective implementation of the SDGs through their national action plans.

• Namati is a global organization dedicated to putting the power of the law in the hands of the people. It facilitates a Global Legal Empowerment Network that brings together 1,500+ organizations and 6,000+ individuals dedicated to grassroots justice.

Obstacles to the judicial enforcement of the SDGs

Case Study: Improving the Availability of Antiretroviral Medicines: Treatment Action Campaign v. Minister of Health

South Africa: South Africa has more people living with HIV than any other country in the world, affecting around 18 per cent of its population. In 2001, the HIV prevalence rate for pregnant women was an estimated 24.5 per cent, and the number of infants born with the virus totalled about 70,000 a year. Treatment Action Campaign, an AIDS activism CSO, brought a case against the South African Government before the Constitutional Court for the failure to provide access to medicine designed to prevent mother-to-child transmission of the virus during labour. In 2000, the Government announced a programme to introduce the antiretroviral drug Nevirapine in a limited number of pilot projects. Nevirapine can reduce transmission of HIV from mother to child considerably. Treatment Action Campaign, however, argued that these restrictions resulted in unnecessary infections and deaths and were in violation of sections 27 and 28 of the South African Constitution. The Court ruled that the Government must ensure access to the drug for all pregnant women living with HIV and that restrictions of the drug for research purposes denied access to those who could be reasonably included. The judgement is estimated to have saved tens of thousands of lives and served as a significant advance towards the right to access to essential and life-saving medicines. Treatment Action Campaign’s successful claim further served as a catalyst to mobilize efforts around the world for the provision of antiretroviral therapy in developing countries so crucial for progress on SDG 3.20

Case Study: Stakeholder Participation in Determining the Role of a National Caucus in Realizing the SDGs

Kenya: In Kenya, the Parliamentary Caucus on Sustainable Development Goals and Business encouraged the participation of a wide range of actors in developing a strategic plan on the role of the caucus in realizing the SDGs in the country. Through a Stakeholders Workshop and Validation Meeting, the caucus and supporting consultants brought together actors working on SDG implementation and socially responsible business in order to gather feedback and recommendations on the strategic plan. At the Stakeholders Workshop, Namati participated alongside representatives from civil society, corporate social responsibility departments, and other business entities to highlight key priorities and actions the caucus could take to promote progress under various SDGs in Kenya. For example, under SDG 16 it was suggested that a budgetary allocation and other actions by the caucus members could help implement the existing Legal Aid Act and promote access to justice. After incorporation of the workshop outcomes into a feasible strategic plan, the draft was featured at the Validation Meeting for review, discussion and final input. In this way, the caucus has built a plan and established relationships with non-governmental actors that can facilitate further support and collaboration on the SDGs in the country.21